Two more pups had been born as of December 14. The tides are very high, putting them in danger. Even higher 'king' tides are forecast for December 21, 22 and 23 next week. It's good that the pup season is only beginning and the beach is not yet too crowded.

Fortunately, this mother was staying on the ocean side of her pup. This is the first pup born. He's already very fat, so in less danger than a newborn.

There are three pups in this group, with several other mothers-to-be awaiting birth. This group is on the south section, about halfway out on the boardwalk. The senior male is a calm influence. No less dominant males dared to harass the mothers under his protection.

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

Tuesday, December 8, 2015

Seals eat hagfish

From this month's column in The Cambrian:

Elephant seals hunt at 1,000 feet and deeper. Digital

tracking devices make it possible for us to know this, but much of their

feeding behavior remains unknown. It’s too dark down that far for a critter cam

to function. One seal was tracked over 17 hours of her day. Most of her dives

were 20 to 30 minutes long, down to between 1,500 and 2,500 feet. One dive of

over an hour brought her to around 4,000 feet.

Knowing where they go lets us infer that they are eating the

fish and squid that live there. One remarkable video did catch a female

elephant seal eating a hagfish. It was part of a study by Ocean Networks Canada,

which placed a pod at about 3,000 feet deep. The lights and camera went on to

record video for 15 minutes in every two-hour period.

It recorded a huge amount of video, so the word went out to

citizen scientists worldwide to watch the video and report interesting events

recorded. A dedicated 14-year-old boy in the Ukraine watched long enough to see

a female elephant seal slurp up a hagfish!

Hagfish are living fossils, unchanged over 300 million

years. They are primitive fish, with no jaw. Instead, their teeth flex out from

inside their lips. They travel in schools, feeding on the ocean bottom, eating

worms and carcasses of dead animals that float down.

Eating a hagfish is more difficult than she makes it look.

When they are threatened, hagfish nearly instantaneously cover themselves with

sticky, gooey slime. [Do the Ghostbusters know about this?] It’s so thick and

viscous that sharks have to spit them out. The slime clogs their mouths, making

it impossible for them to breathe in water. Elephant seals, even if they took

longer to eat a hagfish and it bloomed its slime protection, could eat them

anyway. They breathe at the surface, so no problem for them.

Improvements in digital technology will undoubtedly advance

so that we can know more about what and how elephant seals eat. For now, we can

be confident that those huge seals resting on the beach represent lots of food

consumed.

Adult males will arrive in December, preparing for the

breeding season to come in January.

Friday, December 4, 2015

First pup!

The first pup of the 2015-16 breeding season was born November 28. Mother and pup are doing fine.

These photos were taken when he/she was two days old. He looks like he's already filling out.

The first birth is usually in late December, but occasionally pups are born earlier. Sometimes they are not healthy and don't survive, but this one is doing fine.

These photos were taken when he/she was two days old. He looks like he's already filling out.

The first birth is usually in late December, but occasionally pups are born earlier. Sometimes they are not healthy and don't survive, but this one is doing fine.

Monday, August 31, 2015

Birdwatching

A good day for birds at the bluff. California gulls as usual, enjoying the company of Heerman's Gulls.

Heerman's Gulls are pretty, with their dark gray plumage and red bills. They migrate up from Mexico at this time of year.

Elegant Terns accompany them. That crest of feathers gives them a jaunty, almost punk look.

Heerman's Gulls are pretty, with their dark gray plumage and red bills. They migrate up from Mexico at this time of year.

Elegant Terns accompany them. That crest of feathers gives them a jaunty, almost punk look.

Friday, August 28, 2015

Sleeping giants

From my column in The Cambria:

Summer vacation draws crowds of visitors to Piedras Blancas

to see the elephant seals. In August, adult and subadult male seals are on the

beach.

Seals are on the beach year round, but as migratory animals

with an annual cycle, they are always coming and going. There are fewer seals

on the beach in summer than other times of the year.

The seals come and go individually. They don’t live in a

group in the ocean, so they make their way back to Piedras Blancas on their own

schedules. A large male may lift his head out to announce himself, perhaps

inviting a sparring match. Fighting isn’t serious at this time of year, with no

females around. Male seals are usually willing to take on a challenger.

These are the biggest, the grand bull seals, weighing as

much as two and a half tons. This is a seal worth seeing. Their pendulous

trunk-like noses, technically proboscis, give them their name.

They come to the beach to molt their skin at this time of

year. Circulation to the hair follicles of the old skin stops, and it simply

peels off. Blood flows to the new skin underneath. Research on harbor seals

using thermal images show that the new skin gets much warmer as blood flows to

it to help it grow.

The seals’ short, stubbly fur looks nearly black when it’s

wet. As the sun dries it, it takes on a lighter brown color. Elephant seals

weren’t hunted for their fur, the way otters and fur seals were. They were

hunted for their blubber, used for lighting oil and machinery lubricant. The

invention of electric lighting and lubrication alternatives from petroleum

helped save them.

Sea otters, whose fur has as many as a million strands per

square inch, rely on their fur for warmth. Those long, waterproof hairs and

soft underfur trap air, keeping their skin dry and insulating them against the

cold water. Sea otters are creatures of the surface, diving down to the bottom

in shallow waters, as far as they can go in one to four minutes. Elephant seals

are creatures of the deep. At 1,000 feet and deeper, the pressure would squeeze

any trapped air out of their fur. As in so many other ways, elephant seals are

adapted to their environment and the niche they occupy.

Males being naturally competitive, they may spar with each

other, on the beach or in the water. Mostly, they sleep. Awake or asleep, they

may hold their breath for ten or fifteen minutes, apnea. That’s normal for

them. As deep divers, they are accustomed to holding their breath. Typical

dives are 20 to 30 minutes, but dives of an hour are typical, and dives over

two hours long have been reported. When they are on land, each breath expends

moisture and energy. Taking fewer breaths, called sleep apnea, is a problem in

humans but for elephant seals on land, it conserves energy.

Watch one or two individual seals to see how long they go

between breaths. Ask a blue-jacketed docent to show you a sample of shed skin.

They are on duty every day.

Tuesday, August 18, 2015

Humpback whales join the seals

John FitzRandolph reports on a young humpback whale in San Simeon Cove:

This story could develop into the North Coast’s marine mammal mystery of the year, and it could prove to be among the most treasured wildlife encounters witnessed here in many years.

For 24 consecutive days (as of Tuesday, Aug. 4), a juvenile humpback whale has been dining on anchovies, sardines and other small bait fish in the San Simeon Cove.

Why has this whale lingered for so many days in the Cove? If there are ample schools of bait fish in the Cove, why aren’t there other whales feeding there as well — as there have been in recent weeks?

Read the rest of his story here.

So this story about humpback whale songs caught my attention: NPR reports:

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/08/04/3749066_humpback-san-simeon-cove-juvenile.html?rh=1#storylink=cpy

Humpback whales don't just sing songs — they compose with the whales around them, singing a song that evolves over time. Scientists didn't know that until they started recording whale sounds in the 1960s and spent years listening. The evolution of this "culture of listening" among researchers is the focus of Morning Edition's weekly summer series, Close Listening: Decoding Nature Through Sound.

Katy Payne, a researcher in acoustic biology at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and her husband, Roger, were the first scientists to realize that the intricate and eerie calls of some humpback whales are actually songs. At a recent visit with Katy in a Cornell sound studio, we played this archived recording of the first whale they ever heard, and she recognized it right away:

"It's the voice of a male humpback whale off shore of Bermuda, in 1964," Katy explained. "It was recorded by a Navy engineer."

Read or listen to the rest of the story here.

This story could develop into the North Coast’s marine mammal mystery of the year, and it could prove to be among the most treasured wildlife encounters witnessed here in many years.

For 24 consecutive days (as of Tuesday, Aug. 4), a juvenile humpback whale has been dining on anchovies, sardines and other small bait fish in the San Simeon Cove.

Why has this whale lingered for so many days in the Cove? If there are ample schools of bait fish in the Cove, why aren’t there other whales feeding there as well — as there have been in recent weeks?

Read the rest of his story here.

So this story about humpback whale songs caught my attention: NPR reports:

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/08/04/3749066_humpback-san-simeon-cove-juvenile.html?rh=1#storylink=cpy

Humpback whales don't just sing songs — they compose with the whales around them, singing a song that evolves over time. Scientists didn't know that until they started recording whale sounds in the 1960s and spent years listening. The evolution of this "culture of listening" among researchers is the focus of Morning Edition's weekly summer series, Close Listening: Decoding Nature Through Sound.

Katy Payne, a researcher in acoustic biology at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and her husband, Roger, were the first scientists to realize that the intricate and eerie calls of some humpback whales are actually songs. At a recent visit with Katy in a Cornell sound studio, we played this archived recording of the first whale they ever heard, and she recognized it right away:

"It's the voice of a male humpback whale off shore of Bermuda, in 1964," Katy explained. "It was recorded by a Navy engineer."

Read or listen to the rest of the story here.

Wednesday, August 12, 2015

Hawaiian Monk Seals

We don't see these rare and endangered seals in California, but their plight concerns us all. John Platt writes about them on Motherboard:

Fans of “The Walking Dead” know it doesn’t take much to start a species-ending apocalypse.

A bite. A scratch. A sneeze. One opportunity to pass a pathogen to someone else and the race toward extinction begins.

That fictional scenario is scary enough, but for some species the reality is even more terrifying—and more likely to happen sometime in the not-so-distant future.

Take the Hawaiian monk seal. Once hunted into near-extinction for their meat and fur in the 19th century, only a few hundred monk seals remained when they were finally protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1976. Intense conservation efforts increased that population to about 1,500 in the 1980s, but the seals still face a precarious recovery. The animals frequently die from entanglement with fishing gear and their population has shrunk to about 1,100 today.

The seals still carry scars from that close call

with extinction. The species has the lowest genetic diversity of any of

the world’s seal species, which means they have a similarly low

resistance to disease. The introduction of a virus to the ecosystem

could easily wipe out the species, said Charles Littnan, lead scientist

for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program.

Around the world, seals and other marine species have experienced several mass die-offs after exposure to morbilliviruses, a group of diseases that include canine distemper and the measles.

“The destructive force of a disease is comparable to nothing,” Littnan said. “There is no reason to believe that if morbillivirus comes and gets into monk seals, and this program isn’t in place, that it will be anything less than catastrophic.”

Read the rest of the story here.

Fans of “The Walking Dead” know it doesn’t take much to start a species-ending apocalypse.

A bite. A scratch. A sneeze. One opportunity to pass a pathogen to someone else and the race toward extinction begins.

That fictional scenario is scary enough, but for some species the reality is even more terrifying—and more likely to happen sometime in the not-so-distant future.

Take the Hawaiian monk seal. Once hunted into near-extinction for their meat and fur in the 19th century, only a few hundred monk seals remained when they were finally protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1976. Intense conservation efforts increased that population to about 1,500 in the 1980s, but the seals still face a precarious recovery. The animals frequently die from entanglement with fishing gear and their population has shrunk to about 1,100 today.

|

| Hawaiian Monk seal mother and pup. NOAA photo |

This is not a theoretical danger.

Around the world, seals and other marine species have experienced several mass die-offs after exposure to morbilliviruses, a group of diseases that include canine distemper and the measles.

“The destructive force of a disease is comparable to nothing,” Littnan said. “There is no reason to believe that if morbillivirus comes and gets into monk seals, and this program isn’t in place, that it will be anything less than catastrophic.”

Read the rest of the story here.

Thursday, July 9, 2015

Green Tie

This could be Green Tie, a seal who was entangled in green plastic packing strip back in 2011. He was energetically tussling with other seals in the surf. The scar looks deep, so he is probably not entangled any more.

Welcome back, Green Tie!

Welcome back, Green Tie!

Saturday, June 27, 2015

Good-bye Girls

From my column in The Cambrian:

The crowds thin out in June. Not the people, the seals. The beach that was covered with seals now shows plenty of sand between them. Fewer but larger, the subadult males are on the beach to molt their skin in June and July. The biggest adult males will return in July and August.

Subadult means that they are growing that distinctive elephant seal nose (technically it’s a

proboscis, a long nose), but aren’t fully mature. Their skin peels off once a year, and they spend four to six weeks on the beach looking terrible.

Tap

a Friends of the Elephant Seal docent — a guide in a blue jacket — and

ask to touch some of the shed skin. They carry samples to share with the

public.

The beach is less crowded than the crush of May, when the adult females and the juvenile seals of both sexes rested on the beach for their molt.

They have now left the beach, swimming off in

their new skin. The juveniles will return in September for their fall

rest, but the females won’t come back until January, when they return to

have pups. They have set off for an 8-month migration, to eat and grow

pups.

They’ll be finding fish and squid to eat in deep waters. Wildlife habitat on land is easy to understand. It’s the woods, the plains, the fields. In the ocean, it’s not so obvious. It’s complex and three-dimensional, with zones of different temperature, density and salinity.

Tracking a seal at sea

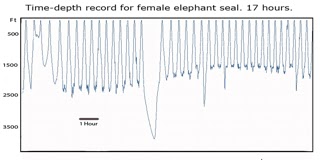

Elephant seals’ main foraging habitat is at 1,000 feet and deeper, dark and cold. In this record of 17 hours in one day of a female elephant seal’s life, she spent most of her time around 2,000 feet. She came to the surface only briefly, for two or three minutes, to breathe, get all the oxygen she needed, and dived down again. Dives deeper than a mile have been recorded.

Most of her dives were 20 to 30 minutes. She coasted most of the way, then the jagged line indicated that she was chasing and catching prey. She came back to the surface and breathed rapidly. Her heartbeat was about 100 beats a minute at the surface, as her body flushed spent carbon dioxide and replaced it with oxygen, in her blood and muscles. Because she needs oxygen to sustain her during those long dives, her muscles have oxygen-carrying myoglobin to keep her supplied.

That accomplished, she dived back down, her heart rate slowing to about 25 beats a minute. Her blood circulation became reduced, giving priority to the brain and heart, but letting the muscles and organs rely on myoglobin.

Then there’s that one long dive, over an hour past 4,000 feet. She could have been escaping from a predator, or she could have been sleeping on the way down.

Filling in the blanks

She doesn’t need to propel herself actively downward. Seals can just coast down through the water, like a falling leaf. Seals have to sleep some time. Since they are continually diving and returning to the surface, perhaps they nap on the way down on some dives.

Exactly how she hunts isn’t yet known. Those big eyes indicate that she’s hunting by sight to some extent. When I first learned about elephant seals, that seemed odd. It’s far too dark to see anything at those depths. Light from the surface penetrates only about 650 feet. But some of her prey is bioluminescent. Those squid flash light. Her sensitive whiskers can detect slight movements and help her find prey, too.

While they are migrating, elephant seals are seldom seen by humans. They’re under water, far from human observation. Digital technology allows us to gather data and use it as a route to understanding these complicated animals, which we observe only when they are on the beach, not in the deep-water habitat where they spend most of their lives.

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/06/24/3694441_elephant-seals-molt-dive-beach.html?rh=1#storylink=cpy

The crowds thin out in June. Not the people, the seals. The beach that was covered with seals now shows plenty of sand between them. Fewer but larger, the subadult males are on the beach to molt their skin in June and July. The biggest adult males will return in July and August.

Subadult means that they are growing that distinctive elephant seal nose (technically it’s a

proboscis, a long nose), but aren’t fully mature. Their skin peels off once a year, and they spend four to six weeks on the beach looking terrible.

|

| A six-year-old faces off with a seven-year-old |

The beach is less crowded than the crush of May, when the adult females and the juvenile seals of both sexes rested on the beach for their molt.

| |

| There's space between seals in June |

They’ll be finding fish and squid to eat in deep waters. Wildlife habitat on land is easy to understand. It’s the woods, the plains, the fields. In the ocean, it’s not so obvious. It’s complex and three-dimensional, with zones of different temperature, density and salinity.

Tracking a seal at sea

Elephant seals’ main foraging habitat is at 1,000 feet and deeper, dark and cold. In this record of 17 hours in one day of a female elephant seal’s life, she spent most of her time around 2,000 feet. She came to the surface only briefly, for two or three minutes, to breathe, get all the oxygen she needed, and dived down again. Dives deeper than a mile have been recorded.

Most of her dives were 20 to 30 minutes. She coasted most of the way, then the jagged line indicated that she was chasing and catching prey. She came back to the surface and breathed rapidly. Her heartbeat was about 100 beats a minute at the surface, as her body flushed spent carbon dioxide and replaced it with oxygen, in her blood and muscles. Because she needs oxygen to sustain her during those long dives, her muscles have oxygen-carrying myoglobin to keep her supplied.

That accomplished, she dived back down, her heart rate slowing to about 25 beats a minute. Her blood circulation became reduced, giving priority to the brain and heart, but letting the muscles and organs rely on myoglobin.

Then there’s that one long dive, over an hour past 4,000 feet. She could have been escaping from a predator, or she could have been sleeping on the way down.

Filling in the blanks

She doesn’t need to propel herself actively downward. Seals can just coast down through the water, like a falling leaf. Seals have to sleep some time. Since they are continually diving and returning to the surface, perhaps they nap on the way down on some dives.

Exactly how she hunts isn’t yet known. Those big eyes indicate that she’s hunting by sight to some extent. When I first learned about elephant seals, that seemed odd. It’s far too dark to see anything at those depths. Light from the surface penetrates only about 650 feet. But some of her prey is bioluminescent. Those squid flash light. Her sensitive whiskers can detect slight movements and help her find prey, too.

While they are migrating, elephant seals are seldom seen by humans. They’re under water, far from human observation. Digital technology allows us to gather data and use it as a route to understanding these complicated animals, which we observe only when they are on the beach, not in the deep-water habitat where they spend most of their lives.

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/06/24/3694441_elephant-seals-molt-dive-beach.html?rh=1#storylink=cpy

Monday, June 15, 2015

June Gloom

That's what we call the fog that is typical for the Central Coast in June. Fuine my me. I'm no more a fan of the hot sun than the seals are.

They rest peacefully on the beach at this time of year.

The females are leaving, so fewer are on the beach, but subadult males are arriving. They will molt for the next month or so, then the adult males will arrive.

Fewer at the top!

His nose is starting to grow, but he is not fully matire. Still, he's a good sized seal!

They rest peacefully on the beach at this time of year.

The females are leaving, so fewer are on the beach, but subadult males are arriving. They will molt for the next month or so, then the adult males will arrive.

Fewer at the top!

| |||

| The nose on this seal indicates that he is about five years old. |

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

New fence

The Civilian Conservation Corps workers built new fences all along the bluff. This is a huge improvement. The fences must have been there since 1998. They were bent and rusted.

Thanks CCC! I hope you enjoyed the time you spent on the bluff helping all our visitors and the seals.

Thanks CCC! I hope you enjoyed the time you spent on the bluff helping all our visitors and the seals.

Tuesday, May 12, 2015

Drone photographs migrating whales

Kathe Tanner writes about the new technology being used to monitor Californa Gray Whales as they migrate along our coast:

As fisheries biologists tally their 22nd springtime count of northbound mother and baby gray whale pairs migrating past Point Piedras Blancas on their way to Alaska, scientists are getting a better look than ever at the cetaceans, thanks to eyes in the sky — in the belly of a $25,000 hexacopter, a kind of drone.

Read the rest at http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/05/07/3623531/whales-enter-the-drone-zone-at.html.

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/05/07/3623531/whales-enter-the-drone-zone-at.html#storylink=cpy

As fisheries biologists tally their 22nd springtime count of northbound mother and baby gray whale pairs migrating past Point Piedras Blancas on their way to Alaska, scientists are getting a better look than ever at the cetaceans, thanks to eyes in the sky — in the belly of a $25,000 hexacopter, a kind of drone.

Read the rest at http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/05/07/3623531/whales-enter-the-drone-zone-at.html.

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/05/07/3623531/whales-enter-the-drone-zone-at.html#storylink=cpy

Saturday, April 25, 2015

Molting

This month's column in The Cambrian:

The seals look like something terrible is happening to them. Their skin is peeling off! Talk about splotchy skin. But for northern elephant seals, it’s the normal, annual molt.

The adult females are on the beach in April and May, accompanied by juvenile seals of both sexes.

Elephant seals, like only one other seal (the Hawaiian monk seal) molt their skin annually in a few short weeks. All other seals molt, but most do so gradually, so it isn’t as noticeable.

A new skin layer forms beneath the old skin. Blood supply to the old skin ceases and the old skin peels off in pieces. Scraps of it skitter across the beach. Friends of the Elephant Seals docents have samples of it to show visitors. Children enjoy handling it. Adults seem to be more dubious, extending a cautious finger for a touch.

The adult males are gone, and this year’s weaners have left on their first migration. The beach is full of seals, but the drama of the breeding season has passed. There are actually more seals on the beach in May than during the breeding season.

The seals stop eating when they are on the beach at the rookery, fasting for that four to six weeks it takes for them to complete their molt.

Females gain weight

When the females were last on the beach, at the end of lactation in February, they were thin. They’d converted their blubber to milk to nourish their pups. They’ve spent the past two months eating and gaining weight.

Now, while they are molting, other invisible, but significant, changes are happening beneath the skin. Before returning to the ocean and leaving her weaned pup on the beach in February, each seal mated to conceive a pup for next season. That fertilized egg divided a few times, then stopped developing. The tiny embryo continued to float free in the uterus, dormant.

The mother-to-be spent the next two months or so feeding freely in her ocean home. When she returns to the beach in April to molt, her body makes the changes needed to have a pup next season.

After she’s finished molting and returns to the ocean, that embryo implants in the uterine wall and begins normal development. Delaying development of the embryo gives her time to gain weight before starting the demands of the next pregnancy.

Staying at sea

Gestation is 7.5 months. When they leave the beach after molting, the expectant mothers will remain at sea until they return to give birth next January.

Delayed implantation is part of a complicated life cycle. Spending most of the year solitary in the water requires different strategies for breeding. So far as their lives are understood, males and females don’t encounter each other except on the beach during breeding season. This is how the species has worked it out.

The 2015 breeding season produced about 4,900 live young-of-the-year, a 9 percent increase over 2014. Fewer females and fewer pups were actually born, but more survived, thanks to the mild winter weather.

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/04/22/3599145_elephant-seals-shed-their-skin.html?rh=1#storylink=cpy

The seals look like something terrible is happening to them. Their skin is peeling off! Talk about splotchy skin. But for northern elephant seals, it’s the normal, annual molt.

The adult females are on the beach in April and May, accompanied by juvenile seals of both sexes.

Elephant seals, like only one other seal (the Hawaiian monk seal) molt their skin annually in a few short weeks. All other seals molt, but most do so gradually, so it isn’t as noticeable.

A new skin layer forms beneath the old skin. Blood supply to the old skin ceases and the old skin peels off in pieces. Scraps of it skitter across the beach. Friends of the Elephant Seals docents have samples of it to show visitors. Children enjoy handling it. Adults seem to be more dubious, extending a cautious finger for a touch.

The adult males are gone, and this year’s weaners have left on their first migration. The beach is full of seals, but the drama of the breeding season has passed. There are actually more seals on the beach in May than during the breeding season.

The seals stop eating when they are on the beach at the rookery, fasting for that four to six weeks it takes for them to complete their molt.

Females gain weight

When the females were last on the beach, at the end of lactation in February, they were thin. They’d converted their blubber to milk to nourish their pups. They’ve spent the past two months eating and gaining weight.

Now, while they are molting, other invisible, but significant, changes are happening beneath the skin. Before returning to the ocean and leaving her weaned pup on the beach in February, each seal mated to conceive a pup for next season. That fertilized egg divided a few times, then stopped developing. The tiny embryo continued to float free in the uterus, dormant.

The mother-to-be spent the next two months or so feeding freely in her ocean home. When she returns to the beach in April to molt, her body makes the changes needed to have a pup next season.

After she’s finished molting and returns to the ocean, that embryo implants in the uterine wall and begins normal development. Delaying development of the embryo gives her time to gain weight before starting the demands of the next pregnancy.

Staying at sea

Gestation is 7.5 months. When they leave the beach after molting, the expectant mothers will remain at sea until they return to give birth next January.

Delayed implantation is part of a complicated life cycle. Spending most of the year solitary in the water requires different strategies for breeding. So far as their lives are understood, males and females don’t encounter each other except on the beach during breeding season. This is how the species has worked it out.

The 2015 breeding season produced about 4,900 live young-of-the-year, a 9 percent increase over 2014. Fewer females and fewer pups were actually born, but more survived, thanks to the mild winter weather.

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/04/22/3599145_elephant-seals-shed-their-skin.html?rh=1#storylink=cpy

Thursday, April 23, 2015

Weddell seals in the Ross Sea

Wildlife photographer John Weller concluded the story he

shared with Cambrian readers last week at his Sunday afternoon

presentation, sponsored by Greenspace — The Cambria Land Trust. In last

week’s Cambrian, he told about being in an underwater ice cave in

Antarctica’s Ross Sea. About 60 people turned out to hear him tell the

story.

After he descended through a hole in the ice, he entered an

ice cave. A second, smaller cave, its entrance only waist-high,

beckoned. He climbed through the low opening.

A beacon of light penetrated a crack in the ice shelf above, creating a gleaming beam, illuminating bottom-dwelling sea creatures, in motion as they climbed on a pile of rocks. Weller unloaded his tripod and camera, no simple task under water, to set up for a particularly beautiful photograph, when he was struck from behind and thrown to the ocean floor.

With his head whirling, and vision blurred, Weller tumbled to the sea floor. A cloud of silt mushroomed up around him. Losing air from his dry suit, he gazed up toward the sea ice, panic setting in.

Above him, he saw a Weddell seal floating, looking down at him. Weddell seals aren’t usually aggressive toward humans, but they are big wild animals. They can be 11 feet long and weigh more than 1,300 pounds. Not the animal to be enclosed with in a small ice cave on a bad day.

Weller scrambled to pull himself together and get out of that cave, but picking up the weight of the tripod and camera without adding air to his dry suit made him crawl toward the exit instead of swimming. Recovering from his daze, he added air to his suit so that he could move better, without losing his equipment.

He made his way out of the cave, past the seal, back to the surface and the safety of the ship. Uninjured but shaken by the experience, he wasn’t sure whether this close call would disqualify him from future dives. Eventually, he shared it with Antarctic ecologist Dr. David Ainley, his mentor on the voyage. By that time, he had become convinced that the seal had never touched him — it had blasted him with a sound so loud that he didn’t recognize it as a noise.

Ainley was intrigued. One of the mysteries of Weddell seals is how they capture prey such as the Antarctic toothfish at depths of more than 800 meters. Seals commonly bring the large fish to the surface by the lip, otherwise uninjured.

Do seals stun their prey with loud sounds blasts? Weller’s experience was consistent with being the target of a 190-decibel sound blast. Ainley is now investigating that possibility. And unlike toothfish, Weller surfaced to tell the tale.

| |

| John Weller's photo of a Weddel Seal in the Ross Sea. |

A beacon of light penetrated a crack in the ice shelf above, creating a gleaming beam, illuminating bottom-dwelling sea creatures, in motion as they climbed on a pile of rocks. Weller unloaded his tripod and camera, no simple task under water, to set up for a particularly beautiful photograph, when he was struck from behind and thrown to the ocean floor.

With his head whirling, and vision blurred, Weller tumbled to the sea floor. A cloud of silt mushroomed up around him. Losing air from his dry suit, he gazed up toward the sea ice, panic setting in.

Above him, he saw a Weddell seal floating, looking down at him. Weddell seals aren’t usually aggressive toward humans, but they are big wild animals. They can be 11 feet long and weigh more than 1,300 pounds. Not the animal to be enclosed with in a small ice cave on a bad day.

Weller scrambled to pull himself together and get out of that cave, but picking up the weight of the tripod and camera without adding air to his dry suit made him crawl toward the exit instead of swimming. Recovering from his daze, he added air to his suit so that he could move better, without losing his equipment.

He made his way out of the cave, past the seal, back to the surface and the safety of the ship. Uninjured but shaken by the experience, he wasn’t sure whether this close call would disqualify him from future dives. Eventually, he shared it with Antarctic ecologist Dr. David Ainley, his mentor on the voyage. By that time, he had become convinced that the seal had never touched him — it had blasted him with a sound so loud that he didn’t recognize it as a noise.

Ainley was intrigued. One of the mysteries of Weddell seals is how they capture prey such as the Antarctic toothfish at depths of more than 800 meters. Seals commonly bring the large fish to the surface by the lip, otherwise uninjured.

Do seals stun their prey with loud sounds blasts? Weller’s experience was consistent with being the target of a 190-decibel sound blast. Ainley is now investigating that possibility. And unlike toothfish, Weller surfaced to tell the tale.

Read more here: http://www.sanluisobispo.com/2015/04/22/3599229_photographer-weller-antarctica.html?rh=1#storylink=cpy

Tuesday, April 14, 2015

Ross Sea photos

Internationally acclaimed photographer John Weller was drawn

to the plight of Antarctica’s Ross Sea after learning this place – the last

large intact marine ecosystem left on earth – was under attack by an

unsustainable fishery. His decade-long journey to tell the Ross Sea story

brought him there four times, including over 50 dives under the ice. He’ll

share photographs and stories from his book The

Last Ocean on Sunday afternoon, 3-4:30 pm, at the Vets Hall. Please join us

to celebrate the incredible natural history and get involved in the movement to

protect the Ross Sea.

Pollution, climate change and overfishing have intrinsically

changed every other part of the world’s ocean. Researchers estimate that humans

have caught as much as 90 percent of the top ocean predators since 1950.

“The ocean seems infinite and immutable,” Weller said. “But

the truth is horrifying. We’ve pushed ocean systems to the brink of collapse

worldwide. The fact that we have damaged the ocean so deeply should be of grave

concern to all people. The Ross Sea story is not just about a fish, or the incredible

organisms that live at the edge of the world. This is our story – the story of

our struggle to become sustainable.”

But Weller believes that conservation in the Ross Sea could

be the start of a tide change in international marine management. Right now a

massive marine protected area in the Ross Sea is under discussion at the

highest levels of government around the world. It would be the biggest marine

protected area in the world.

“Ross Sea protection would require the agreement of 25

nations. Imagine all these voices speaking as one in defense of the ocean. It

has the potential to both protect one of the world’s last great places, and set

the stage for sweeping changes in how we manage oceans all over the globe.

There is a lot riding on the fate of the Ross Sea.”

Despite feeling continually humbled by the extremes of the

Ross Sea, Weller says the most humbling moment occurred on a dive under the

ice:

“Under the ice in McMurdo Sound, there’s a series of

underwater ice caves formed by crushed sea ice. The entrance to the cave

complex is an archway 10 feet tall. Beyond that is a cathedral of light.

‘As I entered this underwater cave, time stood still. It was

as if I were entering an ancient place. And it is. Those caves form every year,

and have for eons. I swam through the first chamber of that cave and was about

to turn around, when I saw another cave, with an archway about waist high. I peeked

through that archway and saw a photograph I knew I needed to take.

‘I swallowed some fear and pushed myself through the archway

into the second chamber of the cave. There, I saw a photograph I will never

forget. Benthic creatures were arranged on a pile of rocks on the sea floor. A crack

in the ice ceiling looked like a plume of blue smoke. I was carrying a tripod

and a camera, so I put it together, working with my camera to get this

photograph.

‘All of a sudden, there was a smack. It felt like something

had hit me in the back of my head with a hammer. My vision blurred, and my

muscles tensed. I rotated in the water, lost air from my dry suit, and found

myself on the sea floor completely dazed, and with a building sense of panic…”

He lived to tell the tale, which he will conclude at his

talk Sunday afternoon.

Weller’s visit is sponsored by Greenspace. $10 suggested donation

at the door. He will sign books for sale after his talk.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)